“….I’ve been up here for seven years now, and I love it, I absolutely love it. Every day I don’t feel older, I feel younger, and I feel like this is my home, and not the ‘outside’, as I call it now….”

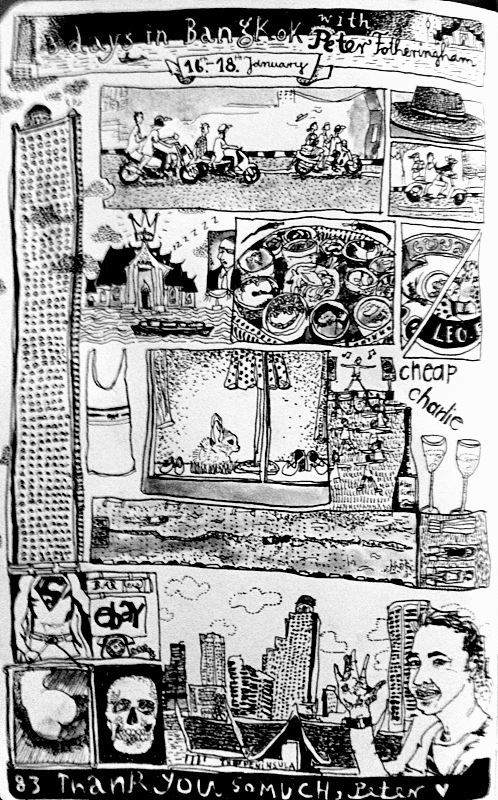

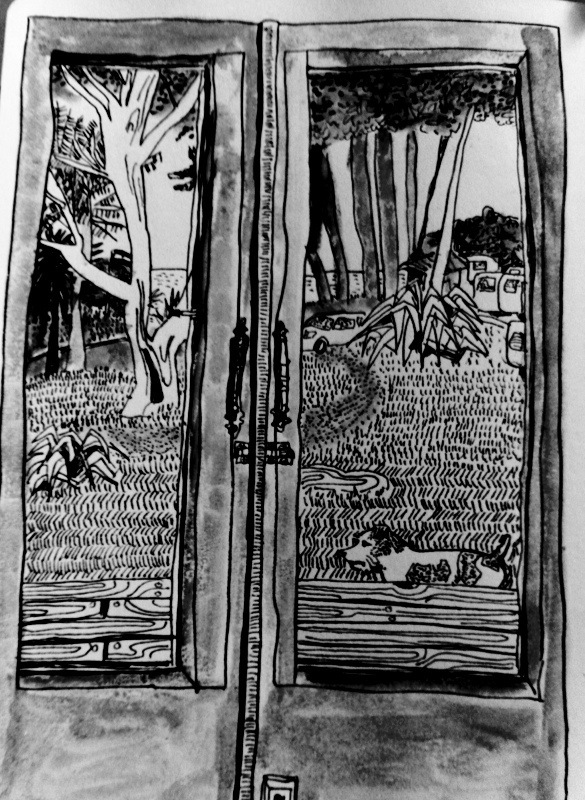

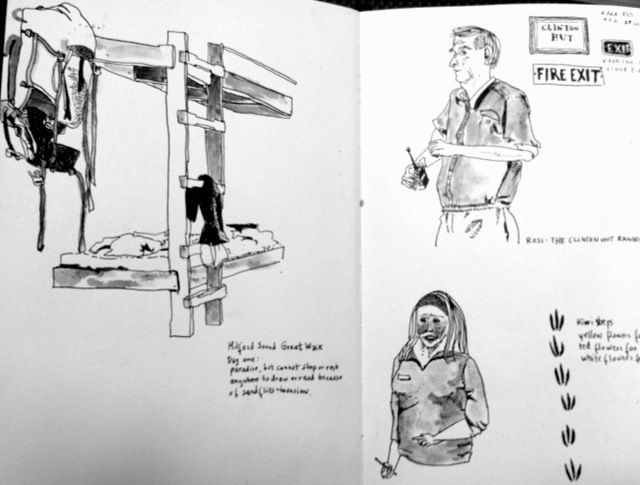

It was the kind of speech that keeps coming back to you after the fact, returning in little loops. It was from Katie, our Mintaro Hut ranger, and it had a ring to it that we couldn’t quite get a hold on. It was like hearing a politician who once believed in his message, and maybe still believes in his message, but has had to repeat it so many times that it becomes too practiced, too polished, to be believed in entirely. Anyone forced to speak in front of other people has this problem, teachers included, but hers had an air of NEED to it, like it was something SHE needed to hear for herself every evening, as justification of her life choice. Being a ranger implies solitude, meaning no significant others, not much extended family, and certainly no children, unless they’re let loose in the wild and allowed to go feral. But society doesn’t accept feral children very well, and society still expects babies from women. And Katie is a woman. So it’s not easy being a female ranger, and Katie’s in a weird position. The hut she’s responsible for is in one of the most astounding places on planet earth – she couldn’t possibly do better than Mintaro – and yet people ask her why she’s there. When she’s alone and has some free time, she writes.

After the speech, Stone Cold Bushwalker raised his hand. “We found some Old Man’s Beard yesterday. I was wondering if any of the rangers had–”

Katie laughed. “You know, I wanted to talk to you about that afterwards, in private, but since you asked…” she smiled at the others in the room, “… it wasn’t Old Man’s Beard you ripped out.”

A big long “OOOOOOOOOHHHHH!” filled up the kitchen, with whoops of laughter piled atop it. The Bushwalker’s face didn’t turn red, it turned pale. He was shellshocked and devastated. It was like watching a priest find out he’d urinated on a cross.

“How much do I owe you,” he flatlined.

The crowd laughed, and Katie said. “It looks a lot like Old Man’s Beard, it really does. It was [whatever] plant, and when it’s juvenile it reeeeeeally looks like Old Man’s Beard.” Bushwalker nodded, looking horrible.

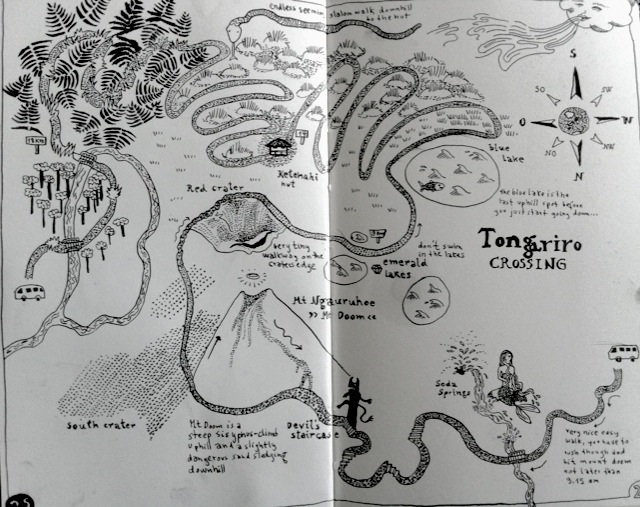

She shifted gears to the next day’s climb. We were to cross Mackinnon Pass. Up top there was a day-hut and a bathroom that was promised to have “The World’s Best View From a Bathroom.”

“And it’s clean,” she promised. “You can just sit on down and… plop!” The crowd laughed – but Katie was serious. “The reason I know it’s clean is ‘cuz I helped clean it out. And you know how we do that?” The crowd didn’t know. “With shovels,” she grinned. “500 lbs.’”

“OOOOOOHHHHH….”

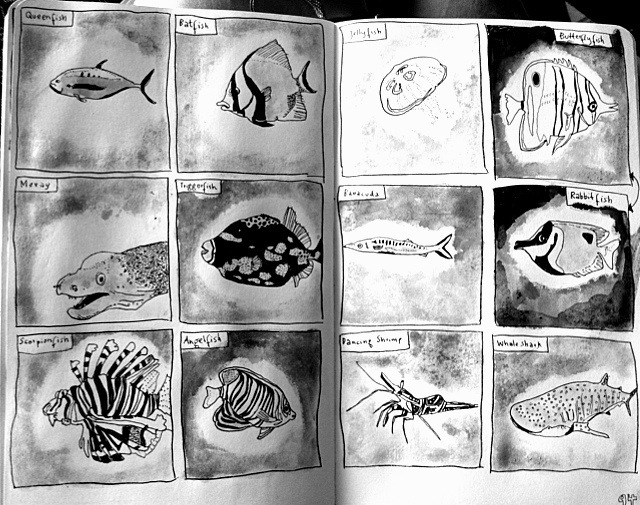

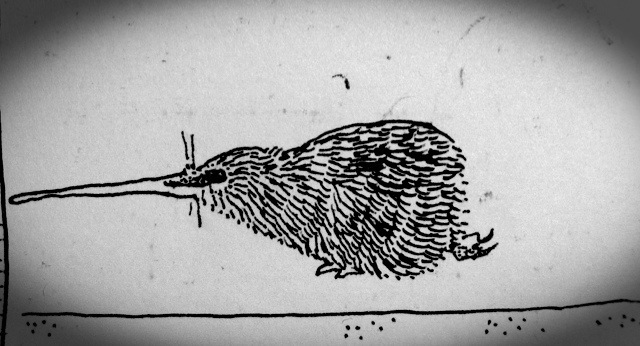

She shifted to Kiwis, meaning the birds, and mentioned that two were in the area. “They’re nocturnal,” she reminded. “And this is proooobably one of your best chances to see them in the wild, just doing what they’re doing. It’s very rare to actually see one, but if you don’t try….”

A woman across from us tried – at 2AM. She hadn’t packed the night before, so she packed at 2AM, why not? As a result we were awake off and on between 2AM and 5AM, when our own alarm went off, and we, too, tried.

It was cold. We had goosebumps, and sometimes shivered. For the first half hour we needed a headlamp, and thereafter we used the cool blue light of the behind-the-mountain sunrise.

Save for a few Paradise Ducks, though, Lake Mintaro was deserted. And at that we headed for Mackinnon pass.

Katie had warned us about the switchbacks, all 11 of them, and from a psychological perspective, I’m not sure if that helped. It’s kind of like a dentist telling you beforehand, “The first part’s gonna hurt, and then the next part’s reeeeeally gonna hurt… but then you’ll be just fine.”

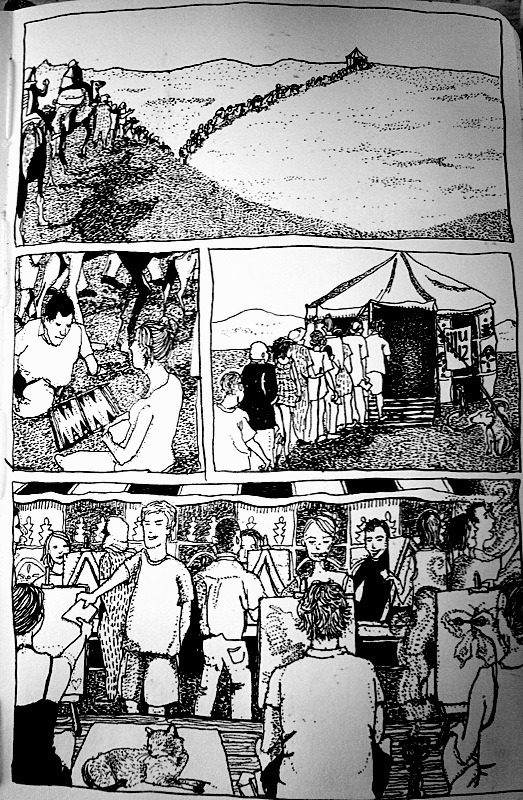

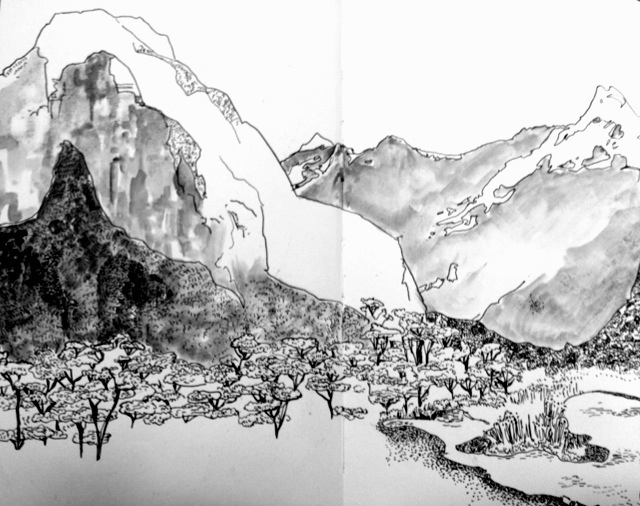

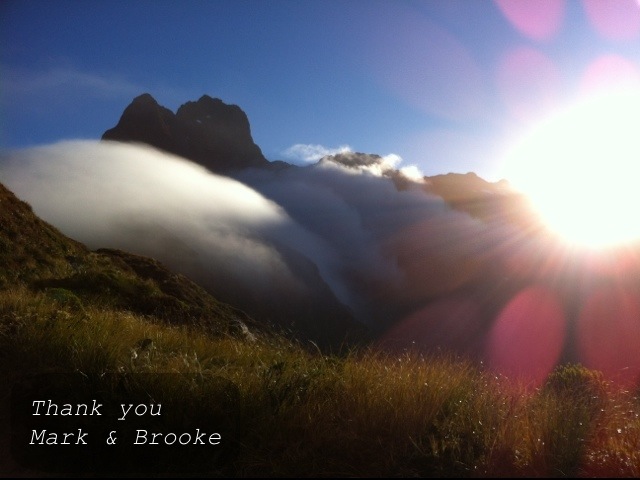

It took two hours, and with the help of the single boiled egg inside our stomachs, suddenly we were at the grassy saddle of the pass, with the sun coming up. We stopped to take pictures of the clouds being sucked over the pass (yesterday’s photo), feeling warm and sweaty and satisfied. 10 minutes later we ascended the pass, and icy hell broke loose.

My layman’s guess is sustained 40MPH (70km) winds, with gusts of 60MPH (100km). The clouds became our fog, and as our sweat cooled, we tried to put pants on over our shorts, our fingers already numbing. (It really is amazing how quickly all this stuff happens.) A few steps later, we dropped our packs again and removed our ponchos. When those were on, we turned into highly flappy, very inefficient sails. But sails we were, nonetheless. “Let’s just get to the goddamn hut,” Antje shivered, and we found the sign on the pass. “Mackinnon Hut – 20 minutes.” WTF? 20 minutes? We were ON the goddamn pass!

Heads down, hoods up, we burrowed into the wind and up the saddle. On the way we passed three Kia birds, who’d also hunkered down atop the pass, watching us with commiseration and occasional attempts to fly. By the time we’d made it, and this will really sound like exaggeration, but it’s not – Antje’s lips were blue, and my fingers were almost useless. In 25 minutes!

“MOTHER NATURE, SHE’S A GOOD OL’ MOTHER, BUT LIKE ALL GOOD MOTHERS, SHE LIKES TO SPANK HER KIDS ONCE IN A WHILE.”

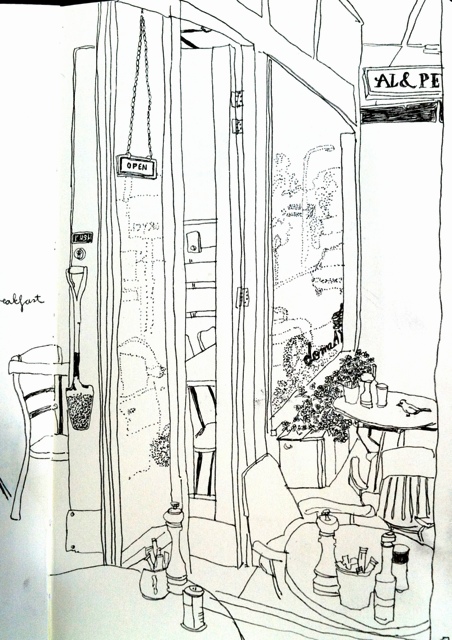

In the hut we made “breakfast”: granola with extra nuts and sliced apples, and powdered molk. Another boiled egg was slurped down, and, when Antje wasn’t looking, some Snickers with chunky peanut butter. Miserably, a perfectly operational gas range sat before us, begging to be used for hot tea. We could not do it. We had no pot. So instead of tea, I sat on Antje’s lap, and felt her shiver.

Five minutes after the hut, and the wind died down. The sun still hadn’t reached the backside of the pass, but the wind had died, and the ponchos made us warm. We slalomed down the mountain, into a bowl with a half-dozen waterfalls, and fresh, drinkable water. A helicopter swooped by, doing all sorts of aerial tricks for the paying passengers, and down, down, down, we continued.

“My knee’s really hurting,” Antje said. It sounded like my old knee injury, and I recommended a few stretches, one of which worked. We stopped when we reached a series of cascading, sandstone waterfalls that, once again, looked like a child’s dream. On the boardwalk above them we took off our packs, raised our feet to the rail, and dreamed senseless thoughts for five minutes in the sunlight.

A ranger walked by with a wink and a faithful Münsterlander, checking tbe traps for stoats.

“Man.” Antje stood up. “My stupid knee.” I looked for a good walking stick, but, also stupidly, they were all rotten. Down, down, down, it continued, and halfway down, we finally had to stop. Antje’s knee was locking up, and the ibuprofen wasn’t doing much.

For those who haven’t had an IT band inflammation, it starts off as a pang and ends up feeling like an exposed nerve. As for the effect it has on the knee, you could say it’s like a motor running out of oil.

The Japanese couple walked up, and the woman asked if she could help in any way. We said no thanks, and they went on. The 2AM kiwi-hunter came up, and, as we exchanged kiwi-hunt stories, it turned out no one had seen a kiwi. Off she went.

The trail finally leveled off to some extent, but Antje was still hobbling. “We don’t have to go to the waterfall,” I said, but she shook her head. “We’re going to the damn waterfall.”

Sutherland Falls is a 1 1/2 hour round-trip extension to the day’s already-very-long trek. Kaite had said we “couldn’t miss it.”

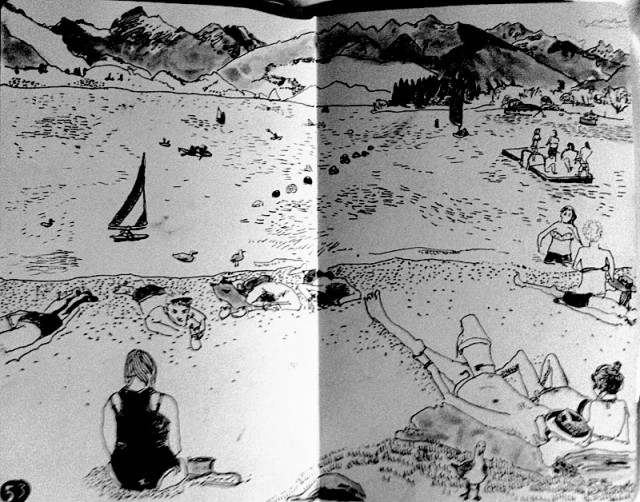

It’s almost 600m (2,000 feet), and we’d never seen a fall like that up close. Though it was “light” due to the recent drought, its power was impressive, like aiming a thumbed-over hose into a bucket. We both swam out in the fall’s general direction, but the blowback kept us away. The Japanese couple were there, and we took turns taking pictures of each other.

Antje’s knee warmed up on the way back, and halfway through we saw the Israelis. “You were swimming?” they asked. We were. “You were with the Koreans?” they asked. Wait, what? Koreans? Why had we thought Japanese? Why had we ASSUMED Japanese? Oh westerners. Good luck to us.

Antje’s knee had stiffened by the time we reached the original trail. Things really weren’t good. She seriously dependent on the stick, a stick that was far too flexible, and was wincing at every tenth step or so. She’d never had the injury before, and was finding out how it injured. From the trail juncture it said “1 hour”, and it took us closer to 2.

Next to Dumpling Hut was another perfect swimming hole, though and Antje used its waters to cool her knee. Insjide our bunkroom was Green Day and his girlfriend, and two things came to light: Green Day needed better deodorant, and they weren’t from Germany after all, but Vienna, Austria. Oops.

During dinner, German girl was cooking for German guy. He walked up from behind, looked over her shoulder, and snarled, “ISN’T IT READY YET?!” She ignored him, and at that point I completely gave up on the redeemability of German guy. I proposed to Antje that we pass around a flyer signed by all that said, “You should break up with him. Sincerely,…”

After dinner, which was instant for us, but included an avocado that was now fermenting, we listened to Amanada, our final Ranger, who implored us to take the next 12 miles, our last, as slowly as we could.

Antje and I would take it slowly.

We’d just had the season’s hottest day, Amanda informed us: 33 degrees, which was 91 degrees Fahrenheit.

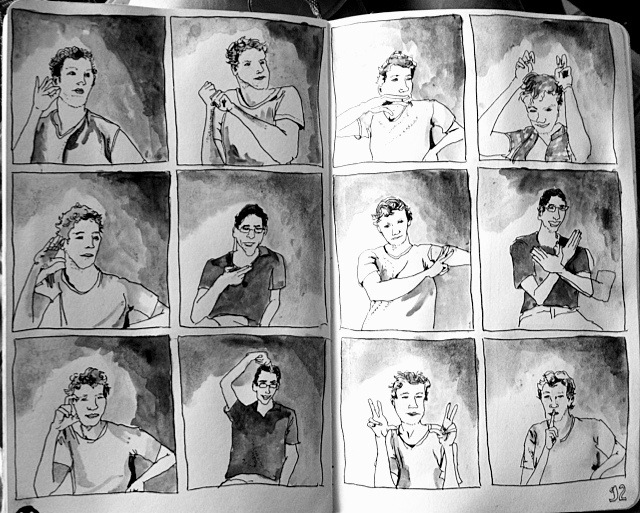

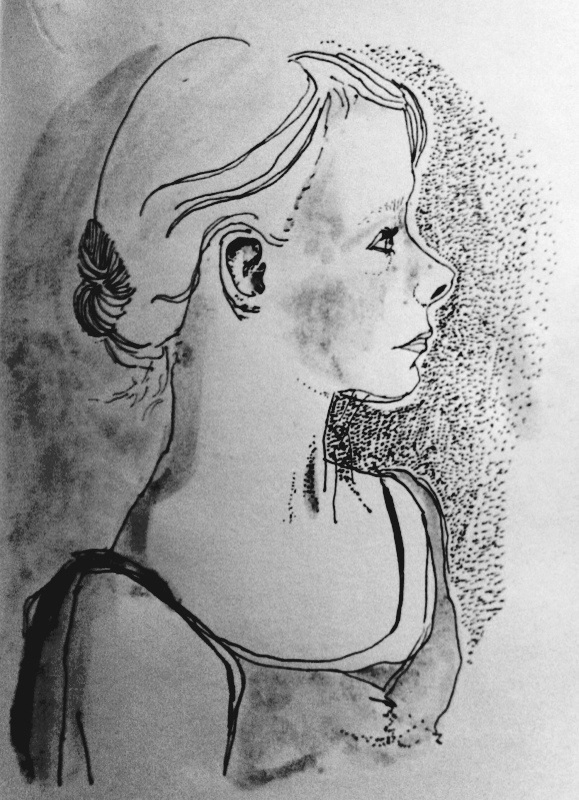

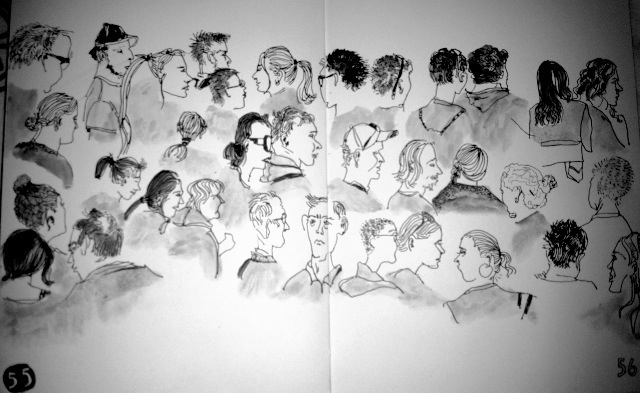

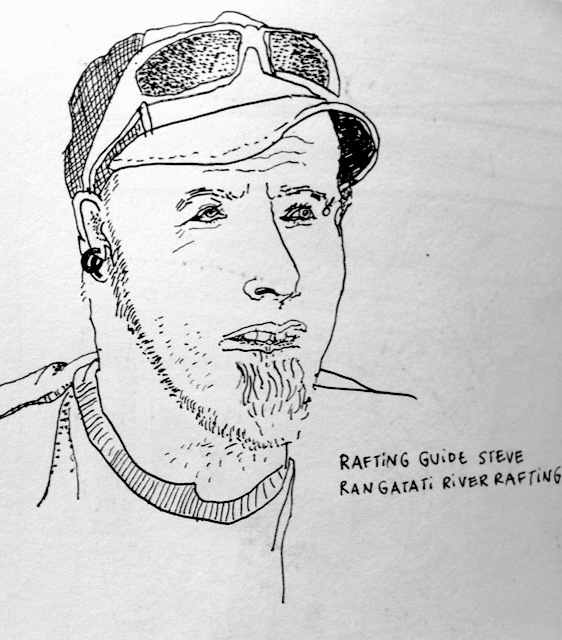

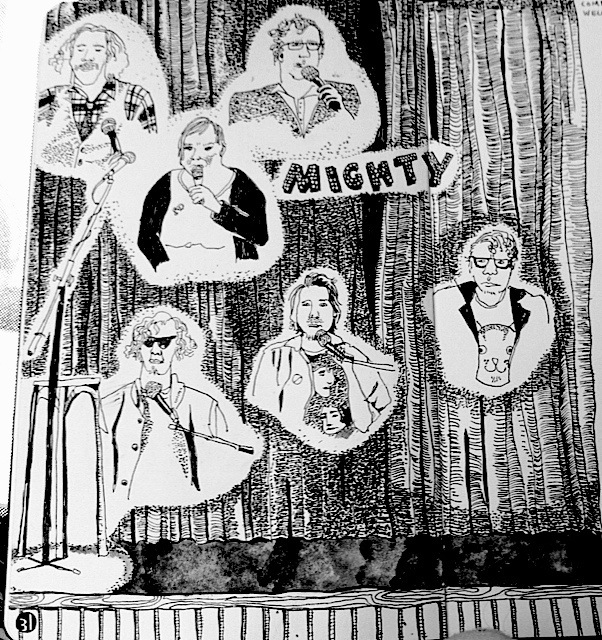

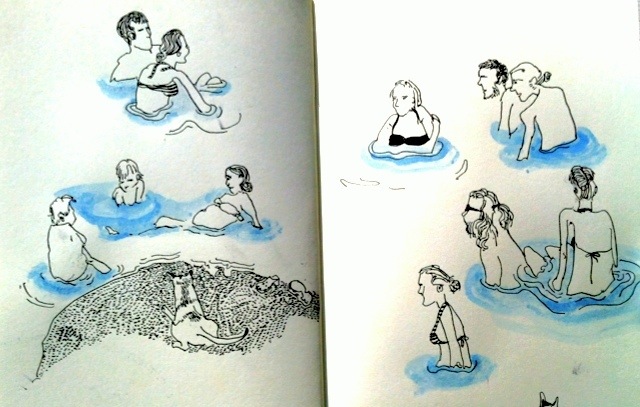

Her speech ended, and NEC boy, with a fair share of nervousness, approached our table and sat down. “Hi,” he said. We said hi back. The whittling, harmonica-playing Israeli engaged him head on in conversation, one man to another, adult-to-adult, all while drawing with a pencil. He had been impressed by Antje’s drawings throughout the trip – even requesting her to draw on his newly whittled backscratcher – and, inspired, he’d been spending the evening drawing… Antje. He laughed at himself for doing it, for such an obvious sign of affection for her, and continued to do so while talking to NEC boy.

“So,” he asked the boy. “Do you ever fight with your brother?”

NEC boy, it turned out, had perfect manners. He never said “Yeah,” or “Yup” – always “yes.” He listened with the type of attentiveness that all human beings wish they could listen with. He’d even stopped slamming doors, thanks to his (attractive) dad’s request to stop doing so. This whole situation was probably a big deal to him – he was talking to so many older people – people who could do whatever they wanted – people who weren’t his parents – and he drank in every word, every movement, every social cue from the “cool kids”.

During a pause we talked about something alcohol related, and NEC boy chimed in, “Since my grandpa paid for this trip, we took him out to a restaurant, and the waiter said, ‘it’s OK for kids to drink alcohol in New Zealand, if their parents are there.’ So my mom let me have a sip of her wine, and I took a big gulp, and it was sooooo disgusting!”

(The grandpa, who was to complete the 33.5-mile journey the next day, was 73.)

In the meantime, the other Israeli had pulled out his Ukelele. I knew he’d brought it on the trek, but had only heard it the evening before, just slightly, as he was playing it on the helicopter pad. While strumming it he explained the difference between a Ukelele and a guitar, and even let me play it for a few minutes. The Swedes sat down, and one asked the same guitar-vs.-ukelele question I’d just asked. Instead of answering, the Israeli completely ignored him and just kept playing. It was rude, but also lovely, and his strumming became more confident.

“You’re really good,” NEC boy said. “My guitar teacher teaches me to play classical stuff. But you’re REALLY good.”

The compliment was so heartfelt, so childishly genuine, that even though it had come from a child, it charmed the Israeli down to his socks. He smiled for five minutes, then hummed along, and then, in the thinnest of voices, began to sing in Hebrew. The other Israeli joined in.

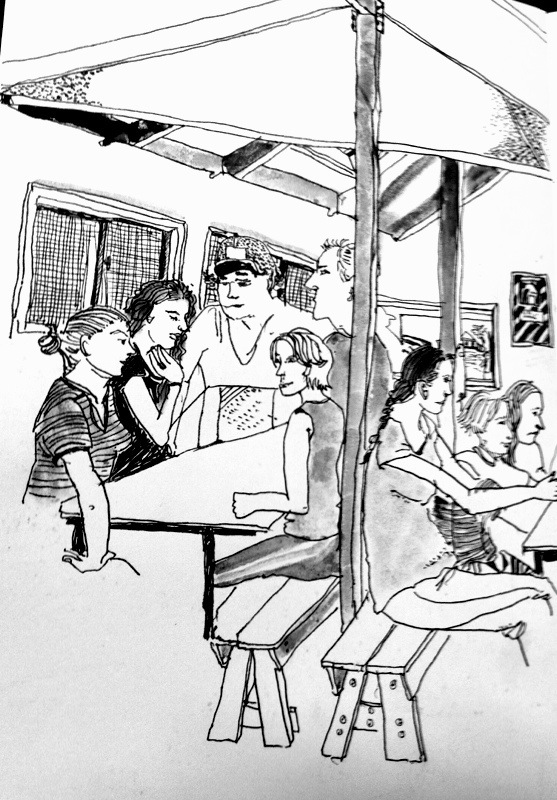

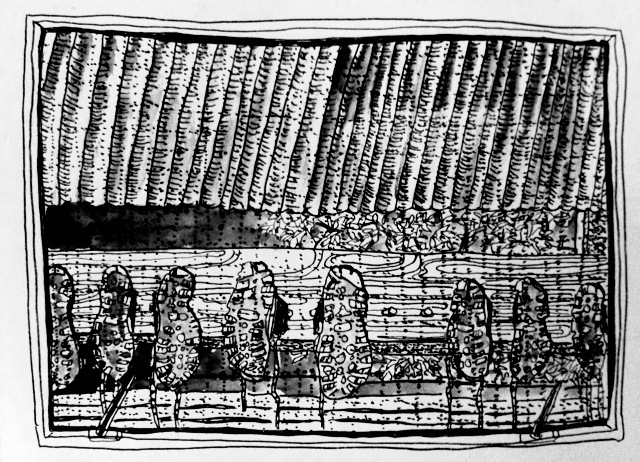

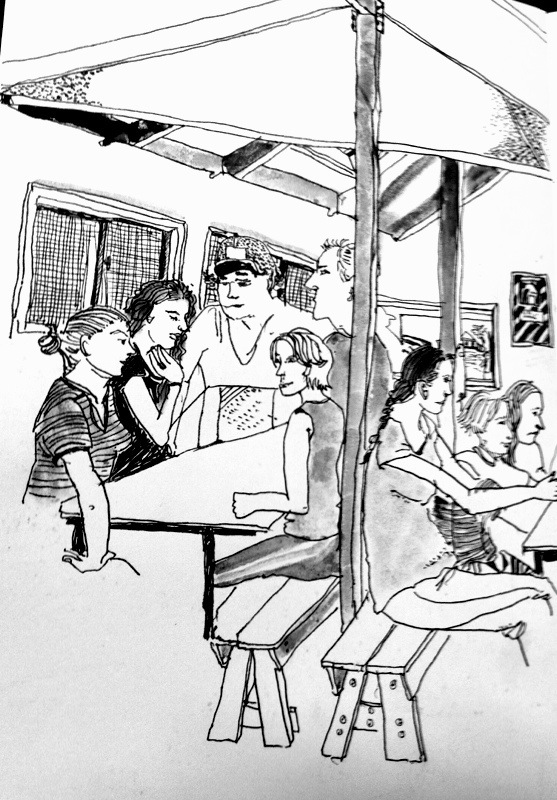

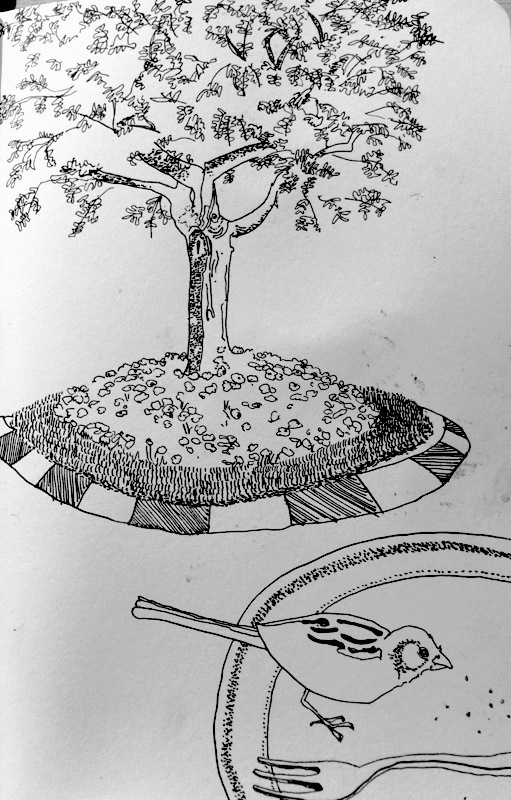

We didn’t take a picture then, but if any single “mental picture” stays stays in my head from that trip, I hope it’s that one, with NEC boy watching the whittling, harmonica-playing, Antje-drawing, and currently-singing Israeli, whose Puerto-Rican-model-looking friend was also singing to the Ukelele, with Biologist girl next to him reading a book about the history of the Milford Track, and Japanese couple, who were now Korean, making another, perfect meal. At just that moment, the Bushwalker group burst in.

“Are you just NOW getting here?” someone asked.

“Of course we are,” he growled, surveying everyone in the entire kitchen. “Don’t see what the bloody rush is all about!”