“Now, a lot of you may be tempted to yell ‘Thar she blows!’” our guide said. “But please don’t do that. Not because it scares the whales or anything, but because it’s wrong.”

The ship, a powerboat catamaran with about 100 seats inside, cruised up and down the waves. It was sea-sicky.

“Today they’re all gonna be male. If you wanna see females and calves, you are definitely in the wrong area. I don’t know if you’ve been for a dip here in Kaikoura, but our water is not tropical.”

Our destination whale was Birdy, a whale whose fluke tips resemble, surprise surprise, a bird.

Earlier, Antje had asked what you call these kinds of whales in English. “Sperm whales,” I said, and she rolled her eyes at what she thought was another really stupid joke that I had wasted more of her time with. When she realized I was serious, her face puckered up, “YUCK.” [German: Pottwal, "Pot Whale"]

On the way we passed a Wandering Albatross, whose four-meter wingspan, our guide said, makes them the “world’s largest bird.” It was a ripe opportunity for a real joke–I should’ve said something like, “But what about Larry Bird?”–but it wasn’t there when I needed it and the tour-guide kept going:

“The average dive-time for Sperm Whales is normally forty-five minutes. So this whale has been down for maybe fifteen minutes, and we’ve got fifteen to twenty minutes to travel out there, so it should be pretty good timing for us.”

A few more Wandering Albatross later, the announcement came. Everyone jumped from their seats simultaneously, creating an instant line. Slowly it inched toward the steel ladder that everyone was apparently having such a terribly difficult getting up. In the middle of all that unsuccess I let a couple in, and they let their children in, and their children let their stuffed animals in. If this goddamned sperm whale wasn’t there when we got there….

THAR HE BLOWS!

I’d always imagined sperm whales, as, uh, moving. Dynamic. Life-like. But this guy was like a jogger after a seriously tough sesh: “Whoooo…. whooaa…. wooow… what a jog… ohhhh… that was good… ohhh… OK now… stretch a bit… OK now… breeeeeathe.” White steam puffed out every thirty seconds or so from his gray-rubber back. Otherwise he didn’t budge. This happened for about ten minutes before the guide got on the intercom.

“OK, folks, get ready. He’s getting ready to dive!”

With the confusingly slow-motion movements of a tremendously huge mammal, the gray rubber back curved, arced down, and the flukes gave a goodbye flap. We gasped collectively and shuffled inside.

Our whale-guide instructed us to look back at Kaikoura’s bay-fringing mountains. One of the peaks, Mt. Munako, is 2,610m (8,000 feet) high. If that mountain could be flipped upside down, she said, that’s how deep a while dives. “When the whale dives to these phenomenal depths all non-vital organs are completely shut down. They’re like living submarines.” Some of my non-vital organs shut down just thinking about it.

Next we made for Tiaki, “The Guardian,” a resident whale who’d been spotted nearby. We pulled up short, though, as another announcement was made. “Just have to wait here for a few minutes, folks. We’re only allowed to have three vessels around a whale. That helicopter should leave any minute here.” Above the helicopter was a Cessna, also filled with whale-watchers, and with both of them circling in the same direction over the whale, and with two very different kinds of engine noise, it all felt a little bit ridiculous, like too much whale-watching, or whale-watching with too much intensity.

The chopper/Cessna combo zipped off to further whales, and our boat nudged forward to Tiaki. A line formed immediately. The ladder was once more ascended with due diligence by all parties. On the positive side, the line was one child shorter: one of the girls had fallen asleep atop her stuffed dolphin. Another memory lost.

From our perspective, Tiaki looked like Birdy, meaning a strip of gray rubber in the waves. But when he, too, gave a good ol’ wave of the flukes, even the layman could tell he was different. Flukes are to whales what fingerprints are to humans. Each one is unique. In other words, if a sperm whale robs a liquor store, he’d better wear a fluke glove. Personally, I’d hoped to see the big bad battering ram of a head, or one, intelligent eye. Apparently they live up to 80 years.

“Trust me,” our guide said, “there is so much that we don’t know about them. A lot of things about sperm whales are based on theory.”

As for the real, quantifiable statistics, they’re horrifying. For most whale species you can take the original population numbers, lop off three zeros, and that’s what you get today. Japan uses a “scientific research” loophole to kill 1,000 every year. That is absolutely vile of Japan. When you’re presented with this information after seeing these animals, it’s hard not to feel a surge of militancy. One group, Sea Shepherd, isn’t militant at all, yet still managed to thwart all but 50 last year.

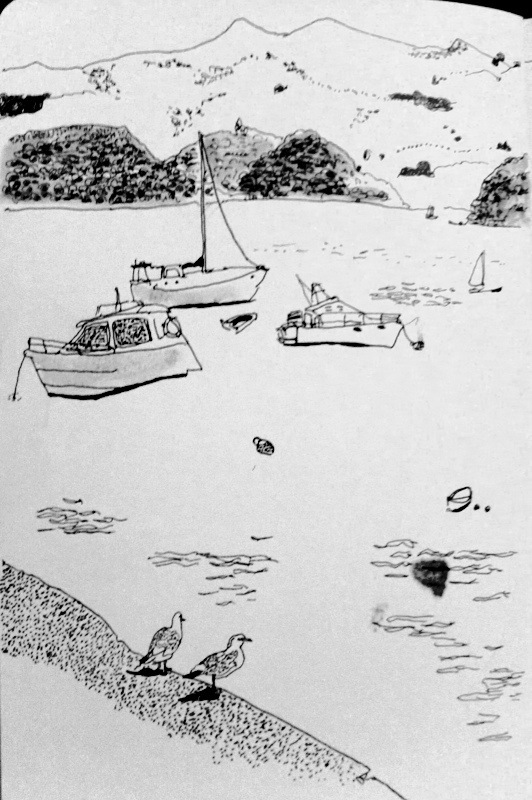

On the way back we stopped for some seal watching, and no one’s hunting these guys. As a result populations have boomed in recent years–above 100,000–and, lying on the sunny rocks, they yawned at us like we were the most boring thing ever.

From Mom:

Great story. I can see why Antje thought you made up the name :-). Now you’ll have to read Moby Dick (or not–way too much information about whales for me :-)).

Love to you both.