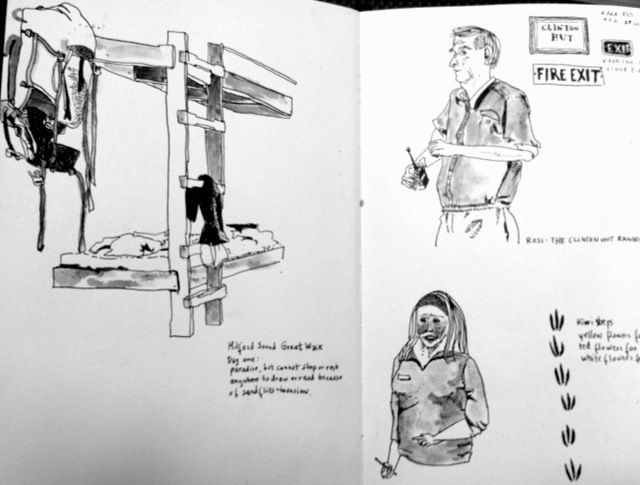

Having walked three-miles, we arrived at Clinton hut, the first on the Milford Track.

Across from our bunks were two Swedes, brothers Hakan and Bengt. I asked Bengt, who’d been living in Sydney for seven years, if he missed home. “No, not really,” he said. His brother was visiting for three weeks, and that was enough of ‘home’.

At dinner, we and the Swedes had our first surprise: there were gas ranges aplenty, and plenty of running water, but no pots. Pots, apparently, were one of those things we should’ve packed in on the trek with us. Everyone else seemed to have read that somewhere. Only we, and the Swedes, hadn’t. “Well, at least we’re in this together,” I said to Bengt. He looked around hopefully and said, “Maybe we can borrow one.”

Luckily, a single, beat-up, communal-looking pot sat under one the ranges. Antje and I used it for a dinner of ramen and baked beans, complimented by a a half-bottle of pinot noir and half-pack of oreos. As the Swedes used the precious pot, two early-twenties Israelis scooted into our table. One was whittling wood with a knife. The other was busy looking like a Puerto Rican model.

But when I said I was from Seattle and lived in Germany, both looked alarmed. “GERMANY? Why do you live in GERMANY?” “Because my wife’s from Germany,” I explained. “So we live there.” Their eyes went from me to Antje, the infernal GERMAN, who smiled and said, “I’m from Germany.”

Silence.

We all kind of looked at each other and tried to smile, but it was as if the table had cracked in two. The situation was gigantic and stupid and totally unnecessary, and I aimed for common ground. “I visited a friend in Israel. He was in the army. We went to a Taglit.” At the mention of the Hebrew word (a Taglit is the the culminating party of a week-long, sponsored trip that any teenaged Jew worldwide can take part in) their eyes lit up. “You are Jewish!” “No, no. We snuck in. Through a side door.” “So you were not invited?” “No, we snuck in.” “Ahhhh. So you had a very good time!” “Of course. There were 4,000 people!” Hakan the Swede asked if they had been in the army, if being in the army was optional. “They do not ask you. They tell you,” the whittling Israeli said.

We were friends, then. Or sort of friends. Or something. The Israelis got up to make tea, using the same beat-up pot that we had. The next day, I realized it wasn’t a communal pot at all. It had been theirs all along. They just watched patiently while everyone else used it.

As they made tea, we talked to the Swedes. Next to the Swedes sat another couple, whose male counterpart I referred to in my head as “Green Day.” The guy had dyed his hair green, bright, bright green, and he had tattoos all over his arms. He even looked like a thicker version of Green Day’s lead singer. He and his girlfriend didn’t introduce themselves at all, and spoke only to each other quietly, in German. Another couple slipped in beside us, also German, and at that point the Ranger strode in.

He was 6’6” tall (2m), 60 years old, and wore hiked up shorts that accentuated the stork-like quality of his thin, white legs. “One look at these,” he joked, “will let you know I’m a darn good ranger.” The whiteboard had mentioned an 8:00 “Ranger Talk,” and after explaining some basic safety concerns, namely fire, he proceeded to explain the next day’s trek, milepost-by-milepost, including the lakes that we were to pass, the orchids we should look for, swimming holes and fishing holes we should watch out for, including the best for trout, a place where the Clinton river branched in two, an old hut that had been overgrown, and was now hard to see, but COULD be seen, if one looked hard enough.

The Israelis were bored. Quietly, but loud enough for our table to hear, the whittling Israeli said sarcastically, “This is a very in-ter-es-ting lecture we are experiencing!” The others smiled or laughed outright, and at this, their opinions on the Ranger, Ross, began to sour.

Ross moved on to a particular flower we were to watch out for, the Mt. Cook Lilly. “Now, the Mt. Cook Lilly is white,” he said. “Does anyone know why it’s white?”

No one knew.

“Does anyone know how they’re pollinated?” he asked.

A late-20s Australian girl raised her hand. “Well, if it’s yellow it’s pollinated by insects, if it’s red it’s pollinated by birds. so white… I guess… is… bats?”

Ross couldn’t hear her.

“By bats?” she said. “Or moths?”

“Moths!” he said. “That’s exactly right!” The girl smiled politely and looked down. Later it came to light that was working on a Ph.D. in Biology.

Ross moved on to the topic that mattered most to him: birds.

He mimicked the different bird calls, bird-by-bird, to a whole lot of laughter; explained which birds might be easily approached and which to wait for; suggested that we stop moving for five minutes and see what happens; talked at length about which birds were now endangered due to non-endemic animals; talked about the way the birds were banded for identification–left leg for female, right for male (“since men are always ‘right’”); lamented their failed attempts at attaching transmitters; told the names of particular birds. “Some of our ducks are named after Aussie cricket players,” he said “since you always have to ‘duck’ when playing against the Aussies.”

Our table, which was back in a corner, had completely given up on Ross. The German guy next to me exhaled loudly, twice, like a spoiled child. The Israelis, too, were no longer listening, and the Swedes were stifling yawns. The whittling Israeli turned to me, “You are paying very good attention,” he said, poking fun. I was. The lecture could’ve used some visuals, but as Antje later said, Ross was deeply, deeply passionate about his work, and passion tends to spread. Ross’s personal mission, the last of his life’s work, you could say, was to save the blue duck.

Blue ducks, he explained have been absolutely ravaged by stoats. A stuffed stoat was passed around, terrifying a Japanese woman, and for good reason: a stoat looks like a squirrel who’s gone so rabid that he chewed his own tale off and ate it for breakfast. Ross explained how the stoat traps worked, and the way he and his colleagues chase ducks into a river net to band them. “They’ve even got one named after me,” Ross said proudly. “He’s got long legs.”

By this point our table was exasperated to the point of mutiny, a classic example of group-think: The whittling Israeli had established that Ross was boring; a few smiles and laughter had followed; no one dared contradict the group’s perceived opinion; they instead reinforced it at every turn; spiral spiral spiral, into blackness.

Fortunately for them, Ross was nearly finished. “Are there any questions?” he asked hopefully. A thick palm shot up, belonging to the gruffest looking man of our 42-person group. His head was shaved, his voice, deep, and his body, thick; he reminded me of Stone Cold Steve Austin, a WWF (or WWE) wrestler. He described his party of three as “bushwalkers”, and said:

“We found some Old Man’s Beard today on one of the trees. Ripped the bloody thing right out and left it right in the middle of the track for you. It’ll take over the whole bloody forest if you let it.”

At this my face went hot. Halfway through the trek I’d found two hunks of moss in the middle of the track, picked them up, and said to Antje, “Look, all we need is some moss glue!” A little while later I tossed them back in the forest.

Ranger Ross asked a few questions about the moss, but otherwise didn’t seem to concerned about Old Man’s beard. He did want to verify where the bushwalkers had left it, though, so that he, or another ranger, could take a look. I almost raised my hand, but didn’t.

At that he finished–to the general applause he deserved.

Afterwards I asked him about a pair of tracks Antje and I had seen in a nearby bog. “Those are Kiwi,” he explained. “Can tell by the hole in the ground. They stick their beak in there, sniff around.” We were thrilled to have discovered Kiwi tracks on our own.

Next, and full of dread, I went to the bushwalker and asked about Old Man’s Beard. His description didn’t match my moss at all, a huge relief. The bushwalker was annoyed, though. “Bloody rangers only care about the birds.”

At that it was time for cleanup, and our second surprise of the day:

No garbage cans!

It made sense, of course. It makes perfect sense. On the 3-mile walk to Clinton Hut I’d been wondering how, logistically, they dealt with all that garbage. Helicopters? The answer was, they didn’t. WE did. Whatever we packed in, we packed out. Duh, duh, duh, duh, duh. Somewhere we’d missed a manual of sorts. But also, I was mad.

The evening before, Antje had mentioned to our excitable hostel-owner, Bob, that we were thinking of bringing a bottle of wine on the trek, a little something to celebrate. “Of course!” he said. “You gotta bring a bottle of wine, everyone brings a bottle of wine for their first night!” It was only three miles, after all, that first day, an easy haul. And thus we brought our half-finished bottle of Pinot Noir.

And now? Now we had a large, empty, heavy glass bottle, one that couldn’t be tossed out.

Which meant we’d be carrying that heavy glass bottle for the next 30.5 miles, up and over a mountain.

Oh bother.

Oh, Bob.

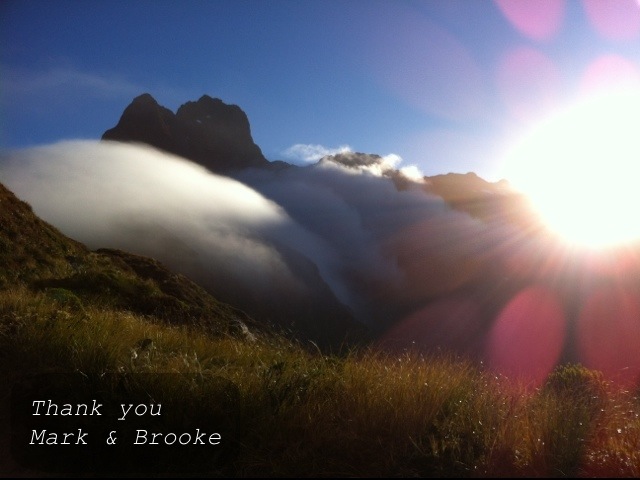

From Mom:

This was hilarious and tender, all in one. Thanks for the beautiful thank you, too, and the great illustrations.

Love to you both.

From Brandon Marchand:

Connor, this is great. Love following your travels. Next time you are in the states, lets grab some beer. I’d love to meet your wife =).

Brandon

(509) 991-6146

From Jeff DeKoker:

Dillons! What an amazing time you’re having! It’s been great catching up with this blog on an otherwise lame weekend filled with jetlag-induced naps. Your writing is hilarious and the sketches are amazing!